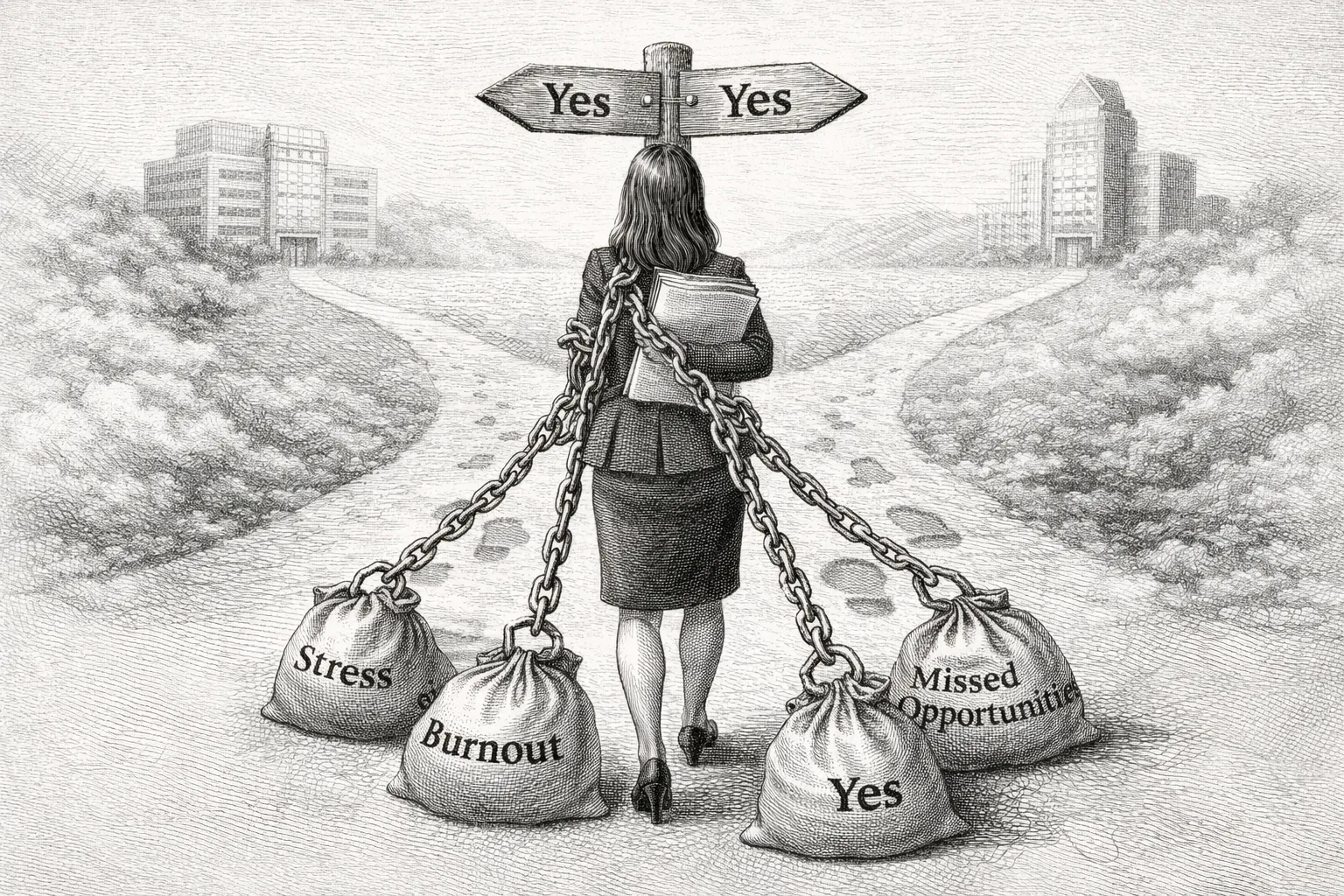

The Career Cost of Always Saying Yes

You pride yourself on being the person who helps. When a colleague needs something, you say yes. When your manager asks if you can take on one more thing, you make it work. When there’s a gap on the team, you step in to fill it. You’ve built a reputation as reliable, collaborative, and willing to go the extra mile. And yet, when you look at your career trajectory, you’re not where you thought you’d be. You’re busy, you’re valued, but you’re not advancing.

Saying yes to everything doesn’t make you indispensable—it makes you invisible to opportunities that could actually move your career forward.

The Problem

Your calendar is completely full. Every day is back-to-back meetings, requests, and commitments you’ve made to other people. You’re helping everyone else succeed, but when you think about your own goals—the project you wanted to lead, the skills you wanted to develop, the strategic work you wanted to do—there’s no time left for any of it.

The requests keep coming because you’ve trained people to expect yes from you. “Can you jump on this call?” Yes. “Can you review this document?” Yes. “Can you help this new team member get up to speed?” Yes. Each individual request seems reasonable, even good. You’re being collaborative. You’re being a team player. You’re building relationships and helping the organization function.

But the cumulative effect is that you’ve become a support system for everyone else’s priorities while your own priorities disappear. You’re not working on high-visibility projects because you’re too busy helping other people with theirs. You’re not developing new skills because you’re spending all your time using the skills people already know you have. You’re not building strategic relationships because you’re always responding to whoever needs something right now.

The painful irony is that your helpfulness is preventing you from becoming more valuable. You’re stuck in a pattern where saying yes keeps you useful in your current role but makes it impossible to grow beyond it. And because you’re so good at saying yes, no one—including you—questions whether this is actually serving your career.

Why this happens to knowledge workers

In knowledge work, being helpful is genuinely valuable. Unlike physical labor where your contribution is easily measured, knowledge work depends on collaboration, information sharing, and coordination. Being the person who helps others makes the whole system run more smoothly. Organizations benefit enormously from people who say yes.

Research suggests that helpful people do receive recognition and positive feedback. Your colleagues appreciate you. Your manager values your flexibility. You might even get good performance reviews that mention your collaborative spirit and willingness to help. But appreciation and advancement are not the same thing.

Many people find that they’re caught in what organizational psychologists call the “helper’s trap.” Because you’re so good at supporting work, you get more support work. Your calendar fills with other people’s urgent needs. Meanwhile, the people who are less helpful—who say no more often, who protect their time, who focus on high-impact projects even when it means letting smaller requests go—are the ones who advance.

For knowledge workers especially, there’s a cultural expectation that being constantly available and responsive is part of professionalism. Saying no feels like you’re not a team player, like you’re being difficult or unhelpful. Remote work has intensified this because the boundaries between work and non-work have dissolved. You can always say yes because you’re always technically available.

The system actively rewards saying yes in the short term—you get immediate gratitude, you avoid conflict, you feel needed—while punishing it in the long term by preventing you from doing the work that would actually differentiate you and advance your career.

What Most People Try

The most common response is to try to fit everything in. Say yes to all the requests and somehow also make time for strategic work. Wake up earlier, work later, optimize your efficiency, eliminate breaks. If you can just be more productive, you can serve everyone else and still pursue your own goals.

This leads to burnout. You can sustain it for weeks or maybe months, but eventually something breaks—your health, your relationships, your ability to think clearly, or your actual performance. And when you’re burned out, you’re even less able to do the strategic work that would advance your career. You’ve sacrificed your future for other people’s present needs.

Some people try to say yes but with boundaries—agreeing to help but limiting how much time or energy they’ll give. “I can review your document but only if you send it by Tuesday.” “I can help with this but I only have 30 minutes.” This is better than unlimited yes, but it’s still fundamentally reactive. You’re still letting other people’s requests dictate how you spend your time, just in slightly smaller chunks.

Others attempt to make their helpfulness more visible. If you’re going to say yes to everything, at least make sure people know how much you’re doing. Track your contributions, mention them in meetings, include them in performance reviews. This sometimes helps with recognition, but it doesn’t solve the underlying problem. Making support work more visible doesn’t transform it into strategic work.

Many people also wait for someone else to recognize the problem and rescue them. Surely your manager will notice how overextended you are and reassign some of your work. Surely someone will see that you’re ready for bigger responsibilities and offer them to you. But managers are busy, and from their perspective, the current system is working. You’re handling everything that’s asked of you. Why would they change it?

The issue with all these approaches is that they treat the symptoms—being too busy, not having enough recognition—without addressing the root cause: you’re saying yes to things that don’t serve your career because you haven’t developed the ability to say no.

What Actually Helps

1. Distinguish between requests that build your career and requests that drain it

Not all yeses are equal. Some requests, if you say yes to them, will teach you something valuable, connect you with important people, or position you for bigger opportunities. Most requests will simply keep you busy doing work that could be done by anyone.

Start categorizing requests before you respond to them. When someone asks you to do something, ask yourself: Does this develop a skill I want to build? Does this increase my visibility with people who influence my career? Does this align with where I want to go, or is it just aligned with where I currently am?

Many people find it helpful to be explicit about this. Keep a short list of your career priorities—the skills you’re building, the projects you want to lead, the reputation you want to develop. When a request comes in, check it against that list. If it doesn’t clearly serve one of those priorities, it’s a candidate for no.

This doesn’t mean you say no to everything that doesn’t directly advance your career. Some requests are just part of being a decent colleague or fulfilling your basic job responsibilities. But there’s a difference between those requests and the constant stream of additional asks that accumulate because you’re known as someone who never says no. The latter category is where you need to start creating boundaries.

Research suggests that people who advance in their careers are not necessarily the most helpful people—they’re the people who are strategic about which requests they say yes to. They build a reputation for being excellent at specific, high-value things rather than being generally available for whatever anyone needs.

2. Practice saying no without guilt or elaborate justification

For people who habitually say yes, saying no feels almost physically uncomfortable. It triggers guilt, anxiety about being perceived as unhelpful, and fear of conflict or disappointment. So when you do say no, you over-explain, apologize excessively, and end up making the other person feel bad, which reinforces your belief that saying no is wrong.

The skill you need to develop is saying no clearly, kindly, and briefly. “I don’t have capacity for that right now.” “That’s not something I can take on.” “I need to focus on other priorities.” No elaborate justification required. No apologizing for having boundaries.

Many people find that they need to practice this with low-stakes requests first. The colleague who asks you to grab coffee, the meeting invitation that’s not essential, the optional project that sounds interesting but doesn’t serve your goals. Get comfortable with the mechanics of saying no before you try it with higher-pressure situations.

It’s also helpful to prepare a few default responses so you’re not making it up in the moment. When you’re caught off guard by a request, your default is probably yes. If you have pre-prepared language for no, you can use it before your automatic yes kicks in. “Let me check my priorities and get back to you” buys you time to actually think about whether you should say yes.

The uncomfortable truth is that some people will be disappointed when you start saying no. That’s okay. Their disappointment is not evidence that you’re doing something wrong—it’s evidence that you’re changing a pattern they benefited from. The people who truly respect you will understand. The people who only valued you for your unlimited availability will need to adjust.

3. Protect time for strategic work before the requests arrive

If you wait until you have free time to work on strategic projects, you’ll never have free time. Requests expand to fill all available space. The only way to ensure time for work that advances your career is to block it before anything else gets scheduled.

This means treating your strategic work like an unmovable commitment. Put it on your calendar first, before you accept any meetings or requests. Ideally, block the same time every week so it becomes a predictable pattern. During that time, you’re not available for requests, meetings, or “quick questions.” You’re working on the projects that will actually move your career forward.

Research suggests that people who advance fastest in knowledge work are often those who have clear, protected time for their highest-value work. Everyone else is constantly reacting to requests, while they’re proactively building the things that differentiate them.

Many people find that they need to communicate this boundary explicitly to their team. “I’m blocking every Tuesday morning for deep work on [strategic project]. I won’t be in meetings or responding to messages during that time, but I’ll be available in the afternoon.” This sets expectations and reduces the guilt when you’re not immediately responsive.

The key is to actually use that protected time for strategic work, not for catching up on the reactive work you didn’t get to. If you block time for strategy but end up using it for email and urgent requests anyway, you’re just moving the problem around.

4. Say yes to opportunities, no to tasks

There’s a useful distinction between opportunities and tasks. Opportunities are things that could genuinely expand your capabilities, your network, or your career options. Tasks are things that need to get done but don’t fundamentally change your trajectory.

When you’re deciding whether to say yes, ask: Is this an opportunity or a task? Leading a new initiative that no one has done before is an opportunity. Attending another status meeting is a task. Speaking at a conference is an opportunity. Reviewing someone’s routine work is a task.

Many people find that they’ve been saying yes to endless tasks while missing opportunities because they’re too busy. The intern who asks you to mentor them—that’s an opportunity to develop leadership skills and build a relationship. The colleague who invites you to collaborate on research—that’s an opportunity to learn something new and potentially publish. The senior leader who asks if you want to present your work to executives—that’s an opportunity for visibility.

But if your calendar is full of tasks you’ve said yes to, you won’t have capacity for opportunities when they appear. And opportunities often come with short windows. By the time you’ve finished all your tasks and have time to pursue the opportunity, it’s gone.

Research suggests that career advancement is much more about capitalizing on a few key opportunities than it is about being consistently helpful with routine tasks. The person who says yes to the right five things will advance further than the person who says yes to everything.

5. Understand that saying no is how you say yes to yourself

Every yes to someone else is a no to something you could be doing for your own development, health, or priorities. When you say yes to helping with someone else’s project, you’re saying no to working on your own. When you say yes to a meeting that’s not essential, you’re saying no to focused work time. When you say yes to being constantly available, you’re saying no to the deep thinking that creates breakthrough ideas.

Framing no as a positive choice—not refusing to help but choosing to prioritize your own growth—makes it feel less like deprivation and more like agency. You’re not being selfish or unhelpful. You’re being strategic about where you invest your finite time and energy.

Many people find that this reframe helps with the guilt. Instead of “I’m saying no because I’m overwhelmed,” it becomes “I’m saying no to this so I can say yes to [strategic priority].” You’re not rejecting the request out of hand—you’re making a trade-off in favor of something that matters more to your long-term goals.

This also helps other people understand your boundaries. When you say “I can’t take that on right now because I’m focused on [project that advances your career],” most reasonable people respect that. They might be disappointed, but they understand the logic. And if they don’t—if they expect you to perpetually sacrifice your own priorities for theirs—that’s important information about the relationship.

The Takeaway

Saying yes to everything feels like generosity and professionalism, but it’s often a form of self-abandonment. You’re prioritizing everyone else’s needs over your own development, everyone else’s projects over your own goals, everyone else’s urgent requests over your own strategic work. The cost isn’t immediately visible—you’re still busy, still valued, still appreciated—but over time, you look around and realize you’ve spent years helping other people build their careers while yours has stagnated. Learning to say no strategically isn’t about being unhelpful or difficult. It’s about recognizing that your time and energy are finite, and the only way to invest them in work that actually advances your career is to stop giving them away to whoever asks. Say yes to opportunities that build your future. Say no to tasks that keep you stuck in your present. And understand that the people who advance aren’t the ones who help everyone with everything—they’re the ones who focus their help on the work that matters most, starting with their own.