Being Reliable Is Not the Same as Being Valuable

You show up on time. You answer every message. You never miss a deadline. And somehow, you still feel like you’re falling behind.

That sinking feeling isn’t because you’re doing something wrong. It’s because you’ve been optimizing for the wrong thing entirely.

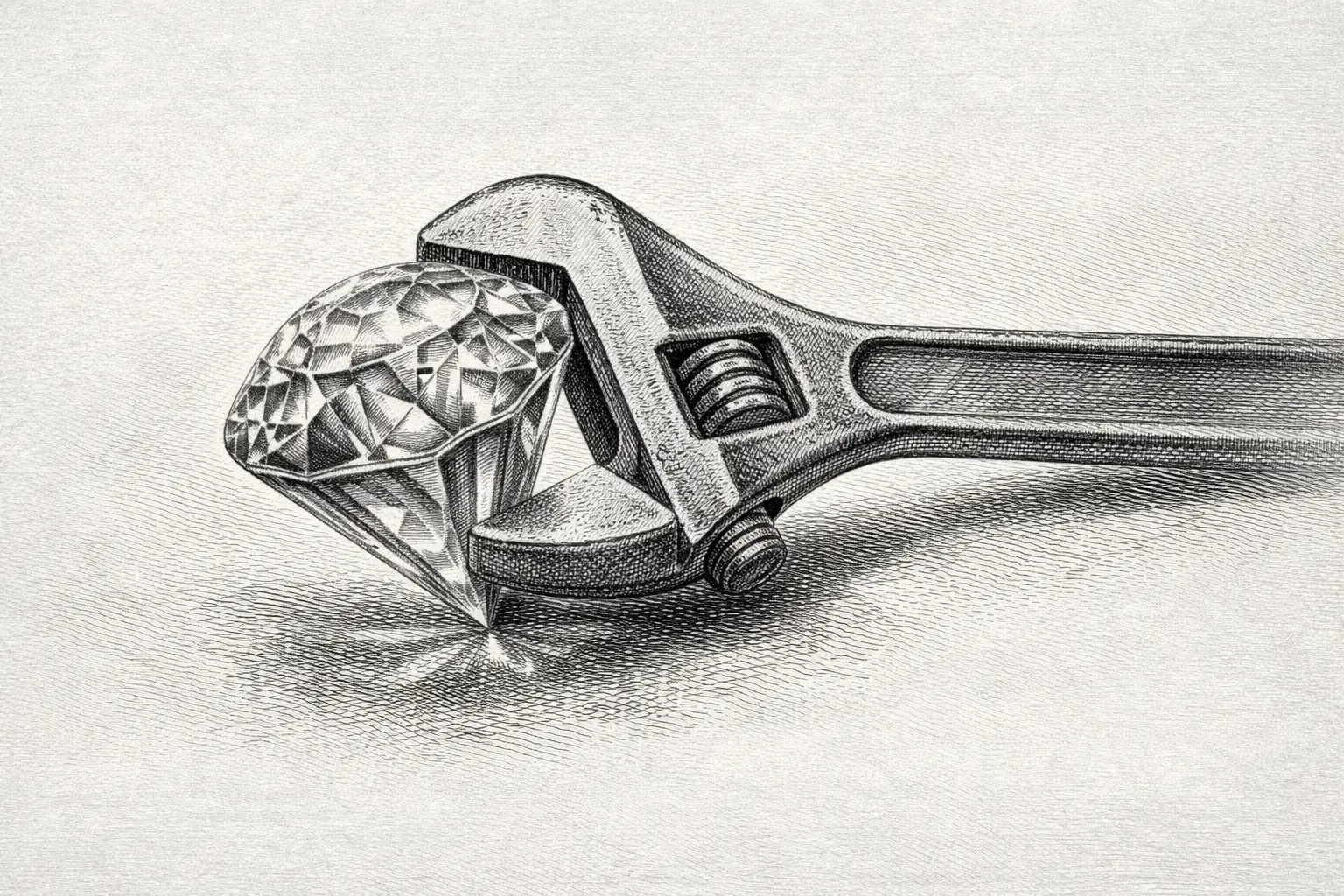

Reliability is the floor, not the ceiling — and confusing the two is quietly burning out the most dependable people in every room.

The Problem

There’s a version of “working hard” that looks indistinguishable from treading water. You’re constantly busy. Your inbox is always clean. Your teammates rely on you for the small stuff — the follow-ups, the scheduling, the tasks nobody else wants to own.

And you do them. Because that’s what good professionals do, right?

The problem is that none of it moves the needle. Not for your career, not for the team, and not for you personally. You’re spending your best hours on things that keep the machine running without ever asking whether the machine is pointed in the right direction.

This isn’t a time management problem. It’s a value problem. And most productivity advice will never tell you that, because most productivity advice is designed to help you do more — not to help you do what matters more.

Why this happens to knowledge workers

Knowledge workers are trained, implicitly and explicitly, to equate busyness with contribution. From your first day at a new job, the fastest way to build trust is to be reliable. Respond quickly. Deliver on time. Don’t drop the ball.

And that training works. It gets you through the early stages. But research suggests that the skills rewarded in your first six months at a role are fundamentally different from the skills that create long-term impact.

Early on, you prove yourself by being dependable. Later, you prove yourself by being indispensable — and indispensability comes from solving problems nobody else can, not from doing tasks nobody else wants to.

Many people find that this shift never gets explicitly called out. Nobody sits down and says, “Now it’s time to stop being reliable and start being valuable.” It just happens — or it doesn’t. And for a lot of high-performing people, it doesn’t, because they never get the signal to change gears.

What Most People Try

When people sense this gap — that nagging feeling that they’re working hard but not growing — the first instinct is usually to work harder. Wake up earlier. Stay later. Add a side project. Optimize the morning routine so you can squeeze out another hour.

This feels productive because it is productive, in the narrowest sense. You’re doing more. But if “more” is still mostly composed of reliable-but-low-value tasks, you’ve just scaled the problem.

The second common move is to get better at time management. Time-blocking, the Pomodoro technique, inbox zero — these tools have real merit. Many people find them genuinely useful for reducing friction in their day.

But time management is a container. It doesn’t change what you put inside it. If you time-block your way through another week of reactive tasks, you’ve just made your reactive work more efficient. The underlying issue — that you’re not spending enough time on high-value work — remains completely untouched.

A third approach is to say yes to everything that looks like an opportunity. A new committee. A stretch project. A cross-team initiative. The logic is sound: more exposure means more chances to demonstrate value.

The problem is that saying yes to everything means saying yes without discernment. And without discernment, you end up spreading yourself thin across a dozen half-finished things, none of which are deep enough to actually move your reputation or your impact.

None of these approaches are wrong. They’re just incomplete. They address the symptoms — the feeling of being stuck, the lack of recognition, the creeping burnout — without addressing the root cause: a failure to deliberately shift from reliability to value creation.

What Actually Helps

1. Do a weekly “value audit” instead of a time audit

Most people, when they try to optimize their week, look at where their time went. That’s useful for efficiency, but it’s the wrong lens for this problem.

Instead, at the end of each week, spend ten minutes answering one question: “What did I do this week that only I could have done?” Not what was urgent. Not what someone asked for. What was uniquely yours to contribute.

If the answer is “not much,” that’s not a judgment — it’s information. It tells you that your week was dominated by tasks that were important but not irreplaceable. Someone else could have done them. Maybe not as well, but well enough.

The value audit isn’t about guilt. It’s about visibility. Once you can see the gap between what you’re doing and what you’re uniquely capable of, you have a concrete starting point. Many people find that just running this exercise for two weeks changes how they approach their to-do list.

How to start: Write down your three biggest tasks from last week. For each one, ask: “If I hadn’t done this, what would have actually happened?” If the answer is “someone else would have handled it,” flag it. That’s your signal.

2. Protect one “deep contribution” block per week — non-negotiable

Reliability work is almost always reactive. Someone needs something, and you deliver it. It’s responsive by nature, which means it fills every gap in your schedule that isn’t already claimed.

Value work is almost always proactive. It requires you to decide what to work on, and then protect the time to do it. Nobody is going to schedule that for you. Nobody is going to remind you.

This is where most people stall. They intend to do deep, high-value work, but they never actually protect the time for it. And because reactive tasks are always knocking at the door, the deep work gets pushed to “next week” indefinitely.

The fix is deceptively simple: block one two-hour window per week and treat it as unmovable. Not a suggestion. Not a “I’ll try to.” A hard boundary, the same way you’d treat a meeting with your most important client.

What goes in that block? Something from your value audit — a problem that’s been nagging at you, a project that could create real impact, an idea you’ve been meaning to develop. The specific task matters less than the act of showing up for it consistently.

3. Learn to say “yes, and here’s what I’d trade for it”

One of the sneakiest traps for reliable people is that they become the default person for new requests. Because they always deliver, people keep coming back to them. And because they want to stay helpful — and because saying no feels risky — they say yes.

The result is a workload that keeps expanding without any corresponding expansion in impact. More tasks, same depth, no real progress on anything that matters deeply.

The reframe isn’t “say no more.” It’s “say yes more honestly.” When someone asks you to take on something new, instead of quietly absorbing it, make the trade-off visible. “I can absolutely do that — if I drop X, or push Y to next week. Which would you prefer?”

This does two things. First, it forces the other person to actually evaluate whether the new task is worth the trade. Many times, when people see what they’re asking you to give up, they realize it wasn’t as urgent as it felt. Second, it teaches the people around you that your time has weight. That it’s allocated, not infinite.

Research suggests that people who make trade-offs explicit tend to be perceived as more strategic and more senior — not less helpful. It’s a subtle shift, but it reframes you from someone who absorbs work to someone who manages priorities.

The Takeaway

Reliability is a strength. Don’t let anyone — or this article — convince you otherwise. But it’s a foundation, not a destination.

The shift from “dependable” to “valuable” isn’t about working harder or working less. It’s about working with more intention — about regularly asking yourself where your unique contribution actually lives, and then protecting the space to do it.

You don’t have to overhaul your entire week. Start with the audit. Block one deep session. Make one trade-off visible. That’s enough to begin moving in the right direction — quietly, reliably, and with real impact.