How Anxiety Masquerades as Distraction

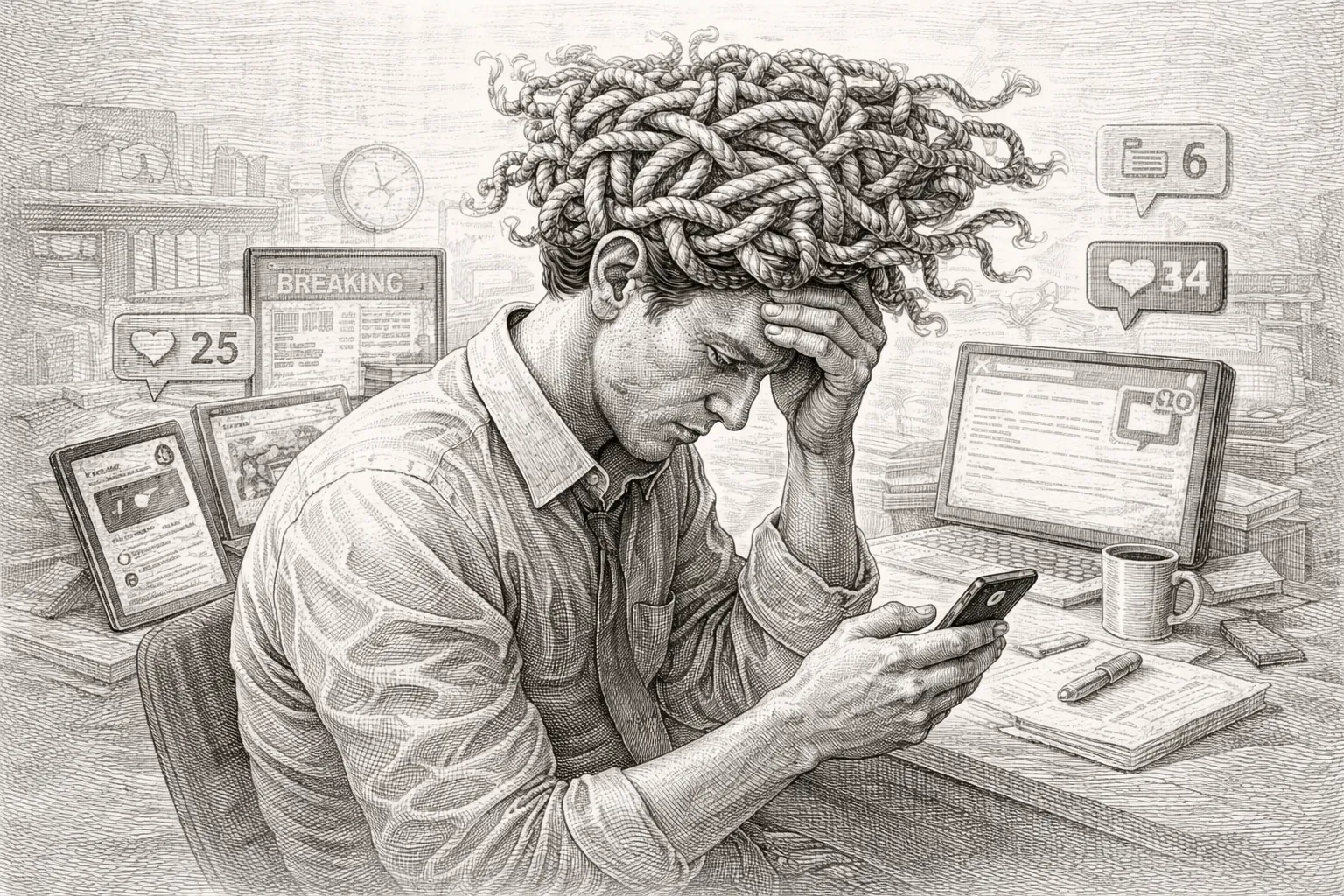

You sit down to work on something important and immediately find yourself checking email, scrolling Twitter, reorganizing your desk. You diagnose this as a distraction problem and try to fix it with focus techniques. But the real issue isn’t that you can’t focus—it’s that focusing on this particular task activates anxiety you’re avoiding.

What looks like distraction is often just anxiety wearing a focus-problem costume.

The Problem

True distraction is when external stimuli pull your attention away from what you’re trying to do. But most modern “distraction” is self-generated: you’re actively seeking alternative activities to avoid uncomfortable mental states. The phone, the email, the sudden urgency of minor tasks—these aren’t interrupting your focus. You’re recruiting them to interrupt it.

The discomfort you’re avoiding is usually some form of anxiety: performance anxiety about the quality of your work, uncertainty anxiety about whether you’re approaching the task correctly, exposure anxiety about being judged on the outcome, or existential anxiety about whether the work matters at all.

Your brain is quite effective at avoiding these feelings. The moment you start to engage with the anxiety-provoking task, your attention conveniently finds something else that needs immediate attention. You’re not weak-willed or undisciplined—you’re efficiently executing an avoidance behavior that successfully reduces discomfort in the short term.

Research suggests that attentional control problems are frequently comorbid with anxiety disorders, and that anxiety-related worry directly competes with task-relevant cognition for working memory resources. When you’re anxious about a task, your brain is already occupied processing the anxiety—there’s less capacity available for the task itself, making genuine focus harder. Then distraction provides relief from both the task difficulty and the anxiety, reinforcing the avoidance pattern.

Why this happens to knowledge workers

Knowledge work creates particularly fertile ground for anxiety-driven distraction because the work involves high uncertainty, delayed feedback, and subjective evaluation. You’re often working on problems without clear solutions, where success isn’t obvious until much later, and where quality is judged by others’ opinions.

This uncertainty is cognitively uncomfortable. When you sit down to write a difficult document, design a complex system, or solve an ambiguous problem, you’re confronting the reality that you might not do it well, you might not know how to proceed, you might waste time on the wrong approach. That’s anxiety-provoking.

Many people find that they can focus easily on routine tasks—updating spreadsheets, answering straightforward emails, fixing known bugs—but struggle to focus on creative or strategic work. They attribute this to the routine work being “easier” or more engaging. But often the difference is anxiety: routine work has clear procedures and predictable outcomes. Creative work is uncertain, which activates anxiety, which triggers distraction as avoidance.

Remote work amplifies this because the lack of external structure means you’re left alone with your anxiety. In an office, social presence and scheduled meetings create forcing functions that push you through anxiety-provoking work. At home, when anxiety hits, there’s nothing stopping you from finding something else to do. The freedom of remote work includes freedom to avoid discomfort indefinitely.

What Most People Try

They try to eliminate distractions. Website blockers, phone in another room, notifications off, clean desk. They treat distraction as an environmental problem—remove the stimulus, and focus will naturally emerge.

But when distraction is actually anxiety avoidance, eliminating one distraction just redirects the avoidance to another outlet. Block social media and you start compulsively checking email. Put your phone away and you start reorganizing files. Remove all digital distractions and you start making coffee, stretching, or staring out the window.

Many people find themselves in an escalating war against distraction: they block more things, create more restrictions, build more elaborate focus environments—and they still can’t focus because they haven’t addressed why they’re seeking distraction. Research suggests that when attentional problems are driven by anxiety rather than environmental factors, environmental modifications provide minimal benefit.

They try to use willpower to push through. If distraction is a discipline problem, the solution is more discipline. Force yourself to stay on task. Resist the urge to check things. Use timers and accountability. Grit your way through the discomfort.

What actually happens: you create a high-pressure situation that increases anxiety, which intensifies the urge to distract, which requires more willpower to resist, which creates more pressure. You’re fighting the symptom (distraction) while amplifying the cause (anxiety). Eventually willpower depletes and you give up completely, often with a side of shame for “failing” at something that “should be” simple.

Research suggests that attempting to suppress anxious thoughts actually increases their frequency and intensity—a phenomenon called ironic process theory. Trying to force focus by willpower when anxiety is the underlying issue often makes both the anxiety and the distraction worse.

They try productivity techniques. Pomodoro timers, time-blocking, the two-minute rule, batching tasks. They approach the focus problem as a workflow optimization challenge. If they just find the right system, focus will follow.

Productivity techniques can help with genuine workflow inefficiency, but they don’t resolve anxiety-driven distraction. You can Pomodoro your way through routine tasks successfully, but the moment you attempt the anxiety-provoking work, the technique fails. Not because the technique is bad, but because the technique wasn’t designed to handle emotional avoidance.

Many people find that they have elaborate productivity systems that they consistently use for low-stakes work and consistently abandon for high-stakes work. The pattern reveals that the problem isn’t productivity methodology—it’s that high-stakes work activates anxiety that triggers avoidance that looks like distraction.

They try to “just start” and momentum will build. The advice is to lower the activation energy: just open the document, just write one sentence, just start for five minutes. The assumption is that starting is the hard part, and once you’re engaged, focus will naturally continue.

But with anxiety-driven distraction, “just starting” doesn’t build momentum—it triggers the anxiety that causes the distraction in the first place. You open the document, feel the anxiety rising, and immediately find something else to do. Starting is hard not because of activation energy but because starting means confronting the uncomfortable mental state you’ve been avoiding.

What Actually Helps

1. Name the specific anxiety you’re avoiding

Distraction is easier to address when you’re honest about what’s driving it. The moment you notice yourself seeking distraction, pause and ask: “What discomfort am I avoiding by not doing this task?”

The answer is usually specific: “I’m afraid this design won’t be good enough.” “I don’t know if I’m approaching this problem correctly.” “I’m worried my writing will sound stupid.” “This task feels pointless and I’m anxious about wasting time.” “I’m afraid of what I’ll discover if I actually look at the data.”

Naming the anxiety doesn’t make it disappear, but it does two things: it reveals that you’re not distracted because you’re undisciplined—you’re distracted because you’re anxious. And it shifts the problem from “how do I focus better” to “how do I work with this specific anxiety.”

Many people find that the act of naming the anxiety reduces its power. Research suggests that affect labeling—putting feelings into words—reduces amygdala activity and helps with emotion regulation. The anxiety doesn’t vanish, but it becomes more manageable when it’s explicit rather than vaguely threatening.

Try this: keep a distraction log for three days. Every time you notice yourself seeking distraction, write down: the task you’re avoiding, and the specific anxiety that arises when you think about doing it. Patterns will emerge. You’ll likely notice that certain types of tasks or certain types of anxiety consistently trigger distraction.

2. Address the anxiety directly before attempting focus

Once you’ve named the anxiety, you can address it rather than avoiding it. This doesn’t mean eliminating the anxiety—that’s often impossible. It means acknowledging it, validating it, and sometimes resolving the underlying concern.

Performance anxiety about work quality: explicitly lower your standards for the first attempt. Tell yourself “this draft will be bad, and that’s fine—I’m just getting ideas down.” Uncertainty anxiety about approach: give yourself permission to try a potentially wrong approach and adjust later. Exposure anxiety about judgment: remind yourself that this is a draft others won’t see yet.

Many people resist this because it feels like “letting yourself off the hook.” But you’re not reducing work quality—you’re reducing the anxiety that prevents you from starting work at all. Research suggests that self-compassion and realistic goal-setting are more effective for task completion than harsh self-criticism.

Some anxiety is pointing to genuine problems that need solving: “I’m anxious about this deadline because it’s actually unrealistic” or “I’m anxious about this project because I don’t have critical information.” In these cases, addressing the anxiety might mean having a difficult conversation, asking for clarification, or adjusting scope. The distraction is pointing to a real issue that focus techniques can’t solve.

Try this before starting anxiety-provoking work: spend two minutes writing out the specific anxiety and what would make it feel more manageable. Often the answer is simple: “I need to remind myself this is a rough draft” or “I need to send a quick message asking for clarification” or “I need to acknowledge that I might need help with this.”

3. Separate productive work from perfect work

Much anxiety-driven distraction comes from conflating “working on the thing” with “completing the thing perfectly.” You think about working on the difficult document, your brain immediately jumps to “can I write this brilliantly?” and when the answer feels uncertain, anxiety spikes and distraction becomes appealing.

Reframe the task from outcome to process: not “write the brilliant document” but “spend 30 minutes thinking about the document in writing.” Not “design the perfect system” but “explore three possible approaches to this problem on paper.” Not “solve this completely” but “understand this better than I do now.”

This isn’t lowering standards—it’s separating the exploration phase (which should be low-stakes and iterative) from the execution phase (which can have higher stakes once you know what you’re doing). Many people find that most of their anxiety-driven distraction happens during the exploration phase when they’re trying to impose execution-level quality on exploratory work.

Research suggests that separating creative exploration from evaluation reduces anxiety and increases creative output. When you’re in exploration mode, judgment and perfectionism are premature—they’re trying to evaluate something that’s not yet fully formed, which creates anxiety that blocks the exploration itself.

Try this reframe for your next anxiety-provoking task: “Today I’m exploring, not executing. I’m thinking about [task], not completing [task]. The goal is to understand the problem better, not solve it perfectly.” This single shift in framing can dramatically reduce the anxiety that triggers distraction.

4. Build anxiety tolerance through gradual exposure

If you consistently avoid anxiety-provoking tasks through distraction, you never build tolerance for the discomfort. The work stays threatening, the anxiety stays high, the avoidance continues. Breaking this pattern requires gradually increasing your capacity to sit with the discomfort.

Start with very short exposure periods: commit to working on the anxiety-provoking task for just five minutes with the explicit goal of noticing and tolerating the discomfort, not completing the task. When the urge to distract arises (it will), notice it, name it (“anxiety is triggering the distraction impulse”), and stay present for just a bit longer.

This is different from willpower pushing through—you’re not trying to force focus, you’re practicing being present with discomfort without immediately seeking relief. Research on exposure therapy suggests that gradually facing feared situations without avoidance reduces anxiety over time as your brain learns the feared outcome doesn’t materialize.

Many people find that their anxiety peaks in the first 2-3 minutes of engaging with the task, then starts to decline if they can stay present. But they’ve never stayed present long enough to notice this because they distract at the first spike of discomfort. Building tolerance means learning that anxiety peaks and passes rather than continuously escalating.

Set a simple protocol: “When I notice distraction urge during important work, I will stay with the task for two more minutes before allowing distraction. I will notice what happens to the anxiety during those two minutes.” Over time, extend the duration. The goal isn’t eliminating the urge to distract—it’s building capacity to continue working while the urge is present.

5. Create structured distraction intervals

Trying to eliminate distraction when it’s serving an anxiety-regulation function is like trying to stop eating when you’re hungry. You’re fighting a legitimate need. A more sustainable approach is to structure the distraction so it provides anxiety relief without completely derailing focus.

Rather than trying to maintain unbroken focus, work in explicit intervals: 25 minutes on the anxiety-provoking task, then 5 minutes of allowed distraction. During the work interval, you’re building anxiety tolerance. During the distraction interval, you’re providing genuine relief. This is different from the Pomodoro Technique—you’re not taking a “break,” you’re taking an anxiety-regulation period.

The key is making the distraction fully allowed during its window. No guilt, no “I should be working.” You’re giving your nervous system permission to discharge the accumulated anxiety. Research suggests that paradoxical interventions—giving yourself full permission to do the behavior you’re trying to reduce—often reduces the compulsive quality of the behavior.

Many people find that structured distraction reduces the intensity of distraction urges during work intervals. When you know relief is coming in 15 minutes, it’s easier to tolerate discomfort now. When distraction is forbidden entirely, every moment of discomfort triggers urgent escape impulses.

Try this: for tasks that consistently trigger anxiety-distraction, set a timer for 20 minutes. Work on the task with full awareness that anxiety will arise and distraction urges will come. When the timer ends, set 5 minutes for complete permission to distract—scroll, check things, do whatever you normally do to avoid. Then repeat. Track whether the pattern changes over several cycles.

6. Distinguish between anxiety-distraction and genuine mental fatigue

Not all “distraction” is anxiety avoidance. Sometimes your brain is actually tired and needs rest. Learning to distinguish between “I’m avoiding anxiety” and “I genuinely don’t have cognitive capacity right now” is critical for appropriate response.

Anxiety-driven distraction has specific markers: it appears immediately when you attempt certain tasks regardless of how much energy you have, it tends to disappear when you switch to less threatening tasks, the distraction has a restless quality rather than a tired quality, and you feel guilty or frustrated about it.

Genuine fatigue distraction is different: it appears after sustained mental effort regardless of task type, it affects all tasks including ones you normally enjoy, the distraction has a foggy quality rather than a seeking quality, and rest actually helps.

Many people respond to both with the same strategy (push through with willpower), which is sometimes appropriate for anxiety-distraction but counterproductive for fatigue. If you’re genuinely tired, you don’t need anxiety management—you need rest. Pushing through fatigue to prove you can focus just depletes you further.

Learn your own patterns: does the distraction appear immediately or after sustained work? Does switching to easier tasks restore focus or does the fogginess persist? Do you feel restless or exhausted? These questions help you determine whether you’re dealing with anxiety management or energy management.

The Takeaway

What appears as a focus problem is often anxiety showing up as avoidance behavior. You’re not weak-willed or uniquely distractible—you’re executing an effective short-term strategy for reducing emotional discomfort. Breaking this pattern requires recognizing the anxiety underneath the distraction, addressing it directly rather than fighting the symptom, separating exploratory work from perfectionistic execution, gradually building tolerance for discomfort, and structuring legitimate anxiety relief instead of trying to eliminate it entirely. The goal isn’t developing superhuman focus—it’s developing the capacity to work while uncomfortable, which looks like focus but is actually something more fundamental: the ability to stay present with what’s difficult.