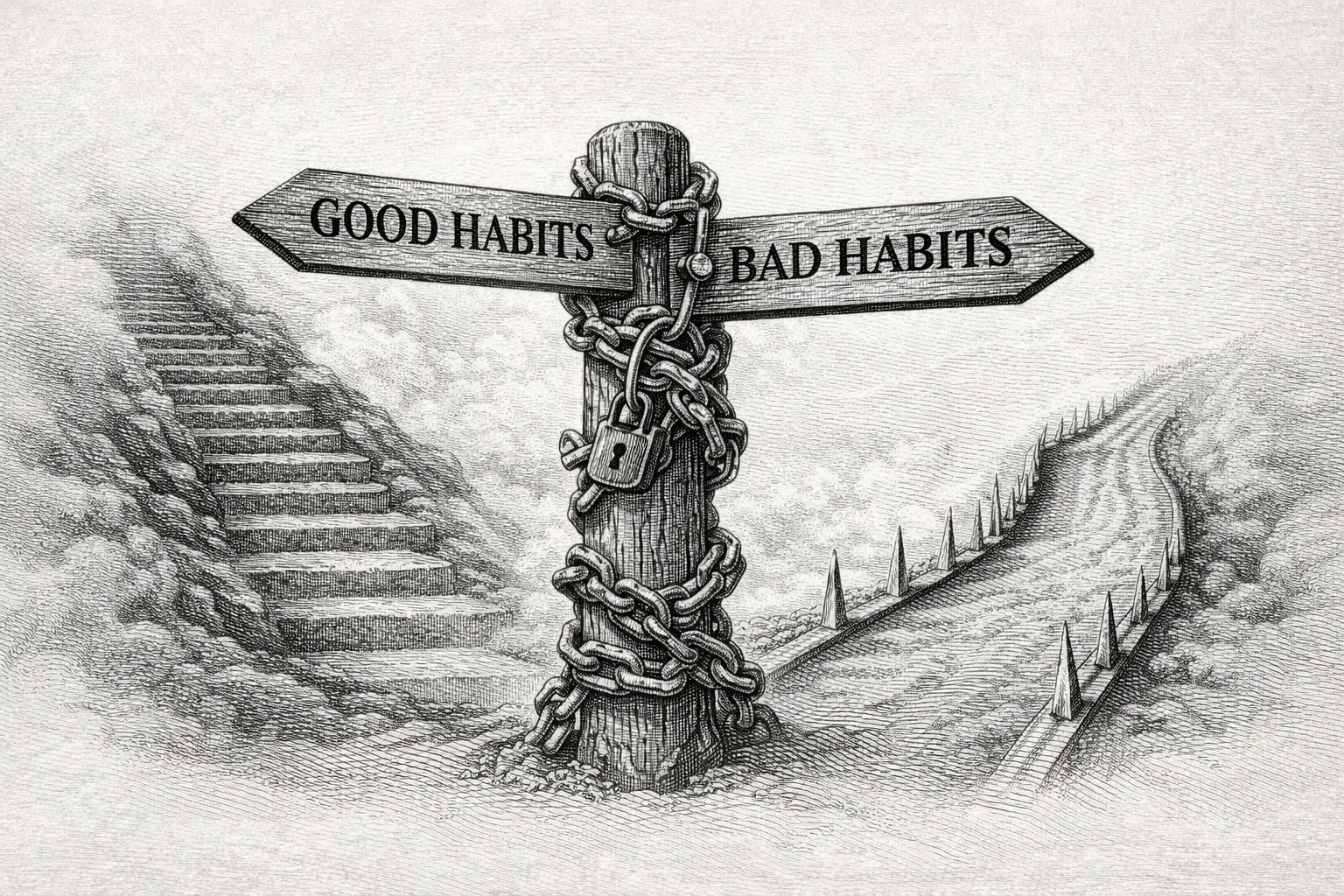

Why Good Habits Feel Harder Than Bad Ones

You decide to start running every morning. The first three days go well. You feel motivated, energized, proud of yourself. Then day four arrives, it’s raining, and you think “I’ll skip today and go tomorrow.” Tomorrow becomes next week. Within a month, the habit is gone. Meanwhile, the habit of checking your phone first thing in the morning—something you never consciously decided to do—is completely automatic and seemingly impossible to break.

Good habits require effort because they’re designed to benefit your future self. Bad habits require no effort because they benefit you right now.

The Problem

You know what you should be doing. Exercise regularly, eat well, read more, practice your craft, maintain relationships. These aren’t mysterious activities—they’re straightforward behaviors that clearly improve your life. And yet, consistently doing them feels like pushing a boulder uphill.

Every morning, you have to convince yourself to work out. Every evening, you have to fight the urge to order takeout instead of cooking. Every weekend, you have to force yourself to call your parents instead of letting another week slip by. The good habits never become effortless. They always require some degree of willpower, some active choice, some mental negotiation.

Bad habits, by contrast, happen automatically. You don’t have to convince yourself to scroll social media—you just find yourself doing it. You don’t debate whether to stay up too late watching videos—you look up and it’s 1am. You don’t carefully consider whether to snap at someone when you’re stressed—the reaction happens before you can stop it.

This asymmetry is exhausting. You’re constantly fighting against your own default behaviors, trying to override automatic patterns with conscious effort. And when that effort fails—which it inevitably does sometimes—you feel like you’ve failed personally. You’re not disciplined enough. You don’t want it badly enough. You’re weak.

But the real problem isn’t your character. It’s that you’re trying to build habits without understanding how habit formation actually works in the brain.

Why this happens to remote workers and knowledge workers

Your brain’s habit system evolved to maximize immediate survival, not long-term wellbeing. When you do something that produces an immediate reward—the dopamine hit from a notification, the pleasure of sugar, the relief of avoiding discomfort—your brain tags that behavior as “good” and makes it easier to repeat.

Research suggests that habits form through a loop: cue, routine, reward. But the crucial part is how quickly the reward arrives. Checking your phone gives you a reward within seconds. The ping sounds (cue), you check it (routine), you see something interesting or feel connected (reward). Your brain learns this loop after just a few repetitions.

Good habits have delayed rewards. You exercise (routine), but the reward—better health, more energy, a stronger body—won’t arrive for weeks or months. Your brain, operating on evolutionary time scales where immediate survival mattered more than long-term health, doesn’t tag this as a strong positive pattern. The behavior doesn’t become automatic because the reward signal is too weak and too distant.

Many people find that modern work culture makes this worse. Remote workers especially face environments designed for distraction. Your phone is always within reach. Your snacks are in the next room. Entertainment is one click away. Every bad habit has been optimized for maximum immediate reward, while every good habit requires you to delay gratification in an environment that makes delay feel intolerable.

Knowledge workers also operate in a context where the outcomes of good habits are abstract and difficult to perceive. If you’re a farmer and you plant seeds, you see crops. If you’re trying to build a habit of deep reading, what do you see? Slightly better thinking that’s hard to measure? It’s not enough to override the immediate pull of easier alternatives.

What Most People Try

The most common approach is to rely on motivation and willpower. You pump yourself up, make ambitious declarations about who you’re going to become, and throw yourself into the new habit with intense enthusiasm. This works for a few days or weeks, powered by novelty and determination.

But motivation is a feeling, and feelings fluctuate. On days when you feel motivated, the good habit is easy. On days when you don’t—which is most days, eventually—the habit collapses. Willpower works the same way. You can force yourself to do something you don’t want to do, but willpower depletes. By the end of a long workday, you have none left for your evening workout or your reading habit.

Some people try to solve this with accountability—telling friends about their goals, posting about their progress on social media, joining groups or challenges. External accountability can help, but it often creates pressure without addressing the underlying difficulty. You end up doing the behavior to avoid shame or maintain an image, not because it’s actually becoming automatic.

Others attempt to make the good habit more enjoyable—listening to podcasts while running, eating healthy food that tastes good, making meditation more comfortable. This helps at the margins, but it doesn’t change the fundamental equation. The habit still requires initiation, still competes with easier alternatives, and still lacks the immediate reward that makes behaviors automatic.

Many people also try to eliminate the bad habits first, thinking that if they just remove the obstacles, the good habits will naturally fill the space. They delete social media apps, throw away junk food, cut toxic people from their lives. This can be useful, but it creates a vacuum without teaching you how to build good habits in their place. You’re left wanting something, reaching for the old pattern, with nothing to replace it.

The limitation of these approaches is that they fight against how habits actually form. They treat habit-building as a motivation problem or a character problem, when it’s actually a design problem. Your brain’s habit system is working exactly as it should—you just need to work with it instead of against it.

What Actually Helps

1. Make the reward immediate and tangible

You can’t change the fact that exercise won’t make you healthy today or that one good meal won’t transform your energy levels. But you can add immediate rewards that your brain can actually register.

This doesn’t mean bribing yourself with treats after every workout—that creates a different kind of dependency. It means finding or creating something genuinely rewarding in the moment of doing the behavior. Maybe it’s the satisfying feeling of checking off a box on a habit tracker immediately after you finish. Maybe it’s a specific song you only listen to during your morning routine. Maybe it’s the sensory pleasure of the activity itself, once you learn to pay attention to it.

Many people find that tracking the behavior itself becomes the reward. Not tracking outcomes—those are still distant—but tracking the act of doing it. You work out, you mark an X on a calendar, and you get a small hit of accomplishment right now. Your brain starts to associate the behavior with that immediate positive feeling, not just with the distant future benefit.

The key is that the reward has to happen every single time you do the behavior, and it has to happen immediately. Delayed rewards—even by a few hours—don’t build the habit loop. Your brain needs the cue-routine-reward sequence to happen tight and fast.

2. Reduce the activation energy to nearly zero

Bad habits stick because they’re incredibly easy to start. Your phone is in your pocket. The TV remote is on the coffee table. The snacks are visible in your kitchen. There’s almost no gap between the impulse and the action.

Good habits usually have friction built in. You have to change clothes to work out. You have to get ingredients to cook a healthy meal. You have to find a quiet space to meditate. Every point of friction is an opportunity for your brain to talk you out of it.

Research suggests that reducing this friction—making the good habit as easy to start as possible—matters more than motivation. Lay out your workout clothes the night before, so putting them on requires no decisions in the morning. Pre-cut vegetables on Sunday so cooking healthy meals during the week is trivial. Keep your meditation cushion in the middle of your living room so you literally have to step over it.

The goal isn’t to make the entire habit effortless—you’ll still have to do the actual workout or meditation. But you want to make starting so easy that you do it before your conscious mind has time to negotiate. Once you’ve started, continuing is much easier. The hard part is always the initiation, and friction makes initiation a decision point where your brain can intervene.

3. Stack the new habit onto an existing automatic behavior

You already have dozens of automatic behaviors in your day. You probably wake up, use the bathroom, make coffee, check your phone—all without much conscious thought. These existing habits are stable anchors. You can use them as triggers for new behaviors.

This is called habit stacking: immediately after you do [existing habit], you do [new habit]. After you pour your morning coffee, you do two minutes of stretching. After you brush your teeth at night, you write one sentence in a journal. After you sit down at your desk, you take three deep breaths before opening your laptop.

Many people find that this works better than trying to build a habit based on time (“I’ll meditate every morning at 7am”) because time is abstract and easy to ignore. An existing behavior is concrete and already automatic. You’re not creating a new trigger—you’re piggybacking on a trigger that already reliably happens.

The new habit has to be small enough that it genuinely fits immediately after the existing one. Not “after coffee, I’ll work out for an hour”—that’s too big. “After coffee, I’ll do ten pushups” is more realistic. Once the small version becomes automatic, you can gradually expand it. But the stacking only works if the new behavior is so small that skipping it would feel harder than just doing it.

4. Understand that good habits never feel effortless—just less effortful

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: most good habits will always require some degree of conscious choice. They might get easier over time—they do—but they rarely become as automatic as bad habits. You’ll probably always have to decide to exercise, even after years of consistency.

This isn’t failure. This is how good habits work. They’re building your future, which means they’re working against immediate comfort. Your brain’s habit system can make them easier, but it can’t make them effortless, because the reward structure isn’t designed for that.

Research suggests that accepting this actually helps. People who expect good habits to eventually feel automatic—the way bad habits do—get discouraged when that doesn’t happen. They think something is wrong with them or their approach. People who understand that good habits always require some effort don’t interpret that effort as failure. They just do the thing anyway.

Many people find that the goal shifts over time. Instead of trying to make the habit feel effortless, they’re trying to make it feel normal. It’s just something they do, like brushing their teeth. It’s not exciting. It’s not particularly enjoyable. But it’s also not a huge negotiation anymore. It’s become part of their identity, even if it still requires a moment of conscious choice.

The Takeaway

Good habits feel harder than bad habits because they are harder—by design. Bad habits offer immediate rewards that your brain’s habit system was built to pursue. Good habits offer delayed rewards that your brain struggles to value. You can’t change this fundamental asymmetry, but you can work with it. Build immediate rewards into good habits, reduce friction to nearly zero, stack new behaviors onto existing automatic ones, and accept that good habits will always require some effort. The goal isn’t to make them feel as easy as scrolling your phone. The goal is to make them easy enough that you do them anyway, consistently, until they become part of who you are rather than something you’re trying to become.